Ian Johns, London Times, 28 Dec 2006 [with my comments in blue]

A rare version of a Bogart and Bacall classic at the NFT shows the pair as you’ve never seen them before

Big-screen romances, real, fabricated and imagined, have often been problematical for Hollywood. Nowadays constant media scrutiny can blur celebrities into a single entity, so Brad Pitt and Angelina Jolie morph into “Brangelina”. Or protestations of love can seem phoney: witness Tom Cruise terrorising Oprah Winfrey’s upholstery with his ardent displays of love for Katie Holmes.

Today’s celebrities also can’t help but keep picking at the scab we call love. Maybe the pool of suitable mates for the rich and famous is smaller than we imagine so you’ll always find Hollywood couples — Charlize Theron and Stuart Townsend, Jake Gyllenhaal and Kirsten Dunst, Orlando Bloom and Kate Bosworth — that are are off, on, off, on and somewhere in between.

Yet there’s one Hollywood romance, whose on-screen chemistry was palpable, that continues to be held in high regard. It’s therefore a surprise to find in next month’s National Film Theatre season celebrating the careers of Humphrey Bogart and Lauren Bacall that they made only four films together. Perhaps it’s because their first two screen partnerships were so sensational. Perhaps that’s why it’s so thrilling that the NFT have got hold of rare footage of the screen couple in one of their most famous films, which very few will have seen before.

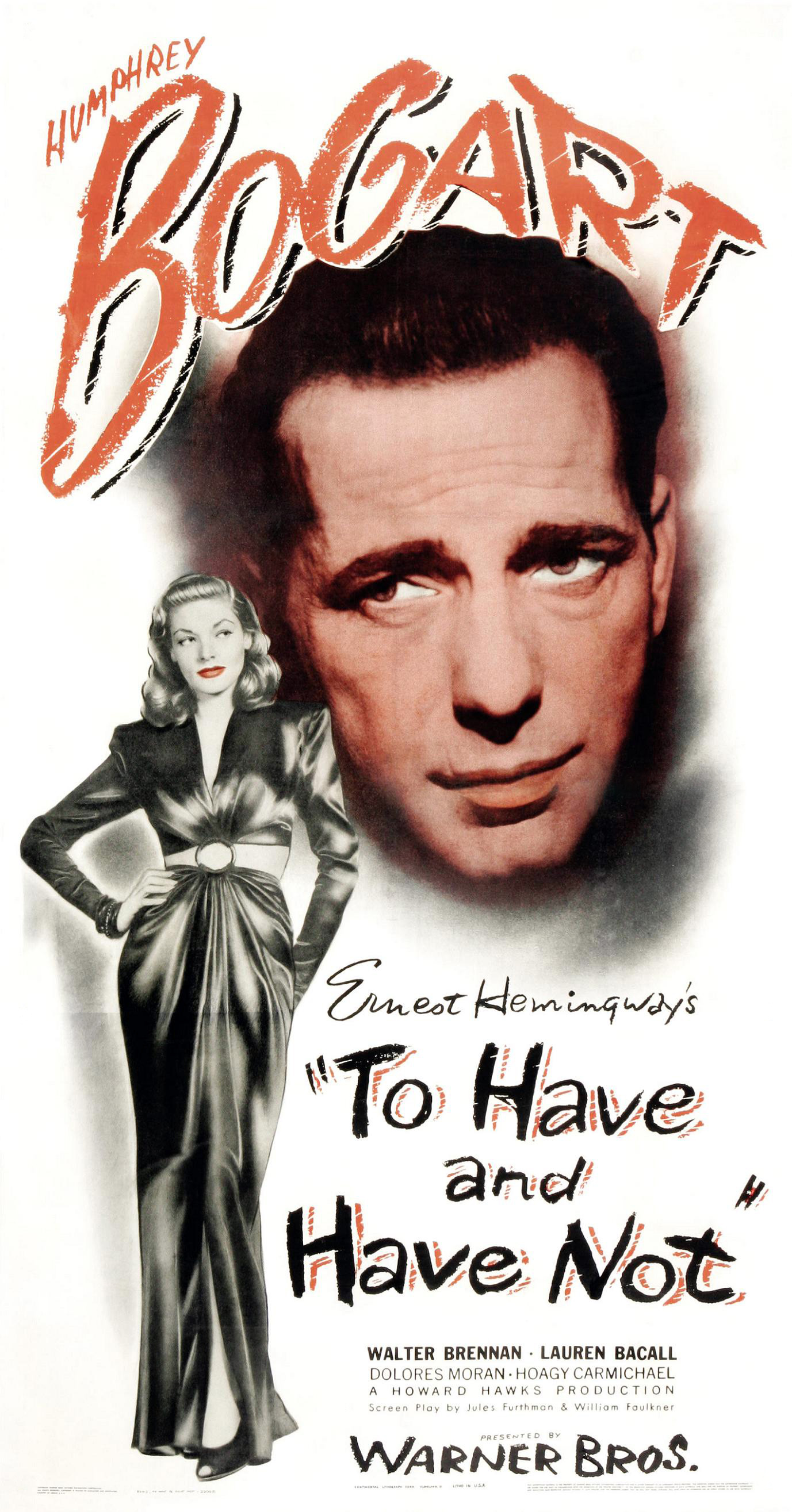

Bacall exploded on the screen in 1944 opposite Bogart in To Have and Have Not, based on an Ernest Hemingway novel that the director Howard Hawks tweaked into a sexier, sassier Casablanca. Bogart plays an expatriate American fishing boat captain lending a grudging hand to French Resistance leaders. Instead of Dooley Wilson crooning "As Time Goes By," it’s Hoagy Carmichael banging out a honky-tonk "Am I Blue." Instead of Bogie offering “Here’ s looking at you, kid” to Ingrid Bergman it’s Bacall, as a nightclub chanteuse, offering Bogie, “I’m hard to get; all you have to do is ask.” [Jean Arthur said virtually the same line to Cary Grant five years earlier at the end of Hawks's Only Angels Have Wings.]

Bacall exploded on the screen in 1944 opposite Bogart in To Have and Have Not, based on an Ernest Hemingway novel that the director Howard Hawks tweaked into a sexier, sassier Casablanca. Bogart plays an expatriate American fishing boat captain lending a grudging hand to French Resistance leaders. Instead of Dooley Wilson crooning "As Time Goes By," it’s Hoagy Carmichael banging out a honky-tonk "Am I Blue." Instead of Bogie offering “Here’ s looking at you, kid” to Ingrid Bergman it’s Bacall, as a nightclub chanteuse, offering Bogie, “I’m hard to get; all you have to do is ask.” [Jean Arthur said virtually the same line to Cary Grant five years earlier at the end of Hawks's Only Angels Have Wings.]Hawks’s wife Nancy [aka "Slim"] had seen Bacall’s picture on the cover of Harper’s Bazaar and recommended that he sign the 18-year-old to a contract. Bacall was so nervous on set that she trembled. To conceal it, Hawks had her lower her head almost to chest level and stare up at her co-star. And so “The Look” was born. Magically, her terror had photographed as insolence, and Warner Bros lost no time in promoting its “Slinky! Sultry! Sensational!” new star.

“Her debut chimed with a changing Hollywood,” says Richard Schickel, the film critic, documentary maker and co-author of the recently published Bogie: A Celebration of Humphrey Bogart (Aurum). “Hollywood was responding to a darker, more cynical wartime mood and Bogart and Bacall fitted into that mood.”

That’s also partly why Bogart had finally broken through as a star after ten years in supporting roles. “In many of his early pictures he was woefully miscast as a ‘tough guy’, when he was essentially a romantic hiding his true nature under a gruff, sardonic shell,” Schickel says. Such qualities can be glimpsed in the rarely seen Black Legion (1937), a social-comment melodrama with Bogart as a digruntled factory worker sucked into a Ku Klux Klan-like vigilantism.

Bogart's early "tough guy" roles include the films The Petrified Forest, San Quentin and The Roaring Twenties - to name just a few. To call Bogart as "woefully miscast" in these movies isn't just untrue, it's insulting Bogart's performances in gangster pictures are on a par with those of the masters of the genre, Edward G. Robinson and James Cagney, particularly in the three pictures I've just named.

Thanks to George Raft turning down the 1941 films High Sierra and The Maltese Falcon, Bogart was able fully to emerge as the laconic, essentially decent loner, a figure he consolidated with Casablanca. “He seemed to embody this mix of dashed dreams and soured expectations but with a dormant idealism that could be reawakened by a good woman or a good idea,” Schickel says. “No wonder disaffected students in the Sixties embraced him.”

By the time he met Bacall he was a huge star. She, by contrast, was an unknown novice for whom Hawks had Pygmalion dreams. He dressed her, advised her and, through The Look and insouciant style he gave her, she turned the notion of a sweet young thing upside down: “If you need anything, just whistle,” she coyly tells Bogart. “You do know how to whistle, don’t you, Steve? You just put your lips together and blow.”

If every scene between Bogie and Bergman exuded sheer romanticism in Casablanca, the Bogie-Bacall encounters in To Have and Have Not ooze carnal complicity.

To Have and Have works almost entirely because of Bogie and Bacall's screen chemistry. I'm pretty sure - I don't know where I read this, so I can't look it up - her role was built up and that her character stayed in the movie longer than originally planned because of their chemistry. Hemingway himself had long said that his novel was unfilmable, and in a way, he was right. The film doesn't exactly fall apart at the end, it just sort of runs out of steam; I can never remember how the film ends. Which at least keeps it fresh from viewing to viewing.

In a small role Bacall stole the show and Bogart’s heart. At the time he was in a turbulent third marriage, to the actress Mayo Methot; they kept a carpenter on standby to repair damage to their home caused in drunken fights. By the time Hawks had reunited Bogart and Bacall for Raymond Chandler’s The Big Sleep (1946), they were about to be married. As gumshoe Philip Marlowe and society dame Vivian Sternwood, the pair had even more of the suggestive banter that lights up To Have and Have Not.

For years, people have puzzled over the arabesque plot involving two blackmail victims, a rich woman and her strange thumb-sucking sister, and a nervy array of nocturnal heavies and six murders. Chandler even joked that he didn’t know whodunnit.

The NFT season includes a 1944 studio draft of the film, which was screened only to servicemen. Although it has more detailed explanations of the famously complex plot, it has fewer of the snappy Bogart and Bacall moments that Hawks shot a year later, including the restaurant scene in which the pair spin an elaborate discussion filled with double entendres about their fondness for racehorses.

In the end Hawks’s released version is less a reading of Chandler than a tribute to the potency of the Bogart-Bacall partnership. Even Leigh Brackett, who co-wrote the screenplay, said that it wasn’t so much the dialogue but the electricity of the two stars working in complete accord that propelled the film to classic status. Catch Bacall’s turn as a spoiled, acid-tongued but likeable woman in the Paul Newman detective drama Harper (1966) and it could be a homage to her younger self in The Big Sleep.

Hawks loved the film, but hated Bacall’s continuing romance with Bogart. No longer able to influence her, he had Warner Bros sell her, for a reputed $1 million, which turned her into a contract player who was assigned to whatever came along. Her subsequent career often involved suspension by the studio for refusing roles. [I think he means that Hawks sold Bacall's contract to Warners - otherwise, that sentence makes no sense.]

Away from the film set, she was a devoted wife, caring and comforting Bogart when needed. “I married a man who expected me to be there,” she once said. She kept working in supporting roles — How to Marry a Millionaire and Written in the Wind among them — even though Bogart stipulated that she should not go away on location.

They made two more films together. Dark Passage (1947) is their most conventional movie, a grim film noir with Bogart as a framed fugitive (off-camera for half the running time) and Bacall as the woman who believes in his innocence. [Bogart is off-camera for the first third of Dark Passage because it is shot from his point of view, making it one of the least conventional of the Bogart/Bacall quartet. What the hell is with this guy?] In Key Largo (1948), they are part of a group taken hostage by gangsters in a hotel. Neither star is as intriguing as Edward G. Robinson’s criminal or the Oscar-winning Claire Trevor as his mistress, but the silent rapport between them is fascinating to watch.

“As a couple they accepted each other,” Schickel says. “He never tried to mould her into some womanly ideal that often tempts a husband some 25 years older than his wife. And she accepted his boozy lifestyle with a close circle of friends. I think their stable family life may have even liberated him as an actor. He began to take risks at an age when other stars would have been content with a successful screen persona.”

Schickel cites Bogart as a murder suspect with a frighteningly violent temper in Nicholas Ray’s In a Lonely Place (1950): “What’s remarkable about this performance is that Bogart never judges his character. As far as he’s concerned he’s completely normal, which is why he’s so chilling in the role.”

The film does indeed show that Bogart was a great actor, not simply the icon that he became after his death from cancer in 1957. As Schickel points out, every actor needs at least one film that somehow transcends time and has a continuing claim on the affections of successive generations. For Bogart that film was Casablanca. But he proved on screen that there was more to him than a cynical romanticism artfully wreathed in cigarette smoke.

Casablanca, while Bogart's most famous film, is hardly the only one to pass the test of time. At the very least, I'd add The Maltese Falcon, The African Queen (his only Oscar-winning role, maddeningly unavailable on DVD), Treasure of the Sierra Madre and The Caine Mutiny (which is now out of print), and the lesser-known High Sierra. That's not to say that every Bogart film is an automatic classic. Tokyo Joe was surprisingly uninteresting - especially for a film Bogart produced. And The Two Mrs. Carrolls is to be avoided at all costs.

Bogart and Bacall also appeared in a 1955 television production of The Petrified Forest. Bogie reprised his role as Duke Mantee, which he had created on Broadway 20 years earlier; Bettie Bacall took the role that was played by her childhood idol Bette Davis in the 1936 film.

A theatrical screening of any of these films is an opportunity not to be missed. This is especially true for the 1944 pre-release version of The Big Sleep, as it is currently only available on the region 1 DVD.

2 comments:

Apparently, Charlize Theron & Stuart Townsend are not an on/off couple but rather they are the Strongest couple in Hollywood. It's either you did not know the real stuff or you're just simply fabricating it. Please understand that I'm merely stating the facts with no personal offence to your blog. Thank You.

Your beef is with Ian Johns of the London Times, who wrote the article. I merely re-posted it here.

Post a Comment